Secret Mall Apartment (2024)

The Providence Place mall in downtown Providence, Rhode Island had always been a strange fixture of my childhood landscape. It wasn’t the mall we went to for back-to-school clothes shopping—that would be the South Shore Plaza—nor was it the mall we went to when we wanted to window shop and feel moneyed—that would be the piano-shaped Atrium Mall in Chestnut Hill, now repurposed into medical offices on account of there being another mall directly across the street. You would go to Providence Place for the Dave and Busters, or for the theater with 70mm IMAX projection (this is where I saw Interstellar, just the way Chris Nolan intended), or usually because you were already in town and it was just there. Taking I-95 South from eastern Massachusetts, the first thing to greet you as you enter Providence is the mall’s bizarre parking garage, Colosseum-like in design, wrapping down the entire length of the building and around a curved bend in the road. If this was a place built for humans, it worked hard not to give that impression.

Unbeknownst to preteen me, a group of artists had taken up residence in the mall in the early 2000s. Led by RISD instructor Michael Townsend, a band of eight or so kids found a liminal space beside the parking garage and gradually began to furnish it with Salvation Army furniture until they had built a more or less habitable apartment that they would live in, off and on, for four years. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that the whole movie is somehow a self-reflexive hoax but there’s enough archival footage to lend believability to the story. Townsend was, it turns out, a very early adopter of the film-everything mindset that smartphones encourage, using a point-and-shoot camera hidden in an Altoids tin to document his and his friends’ exploits.

Secret Mall Apartment is a rollicking good time, in the sense that a well-produced video podcast is. The movie ends up being quite a bit more about art and Townsend’s particular artistic practice than about any of the other topics on the table. In the early going, filmmaker Jeremy Workman gives us a glimpse into the history of Providence gentrification, explaining how the mall came into existence and what got snuffed out to make way for it. This is what I want more of, and I’m evidently not alone. Toward the end of the movie, Workman assembles a montage of interview subjects offering their interpretations of what the secret mall apartment was all about. A few of the interviewees suggest that it was an anticapitalist gesture, which sounds right even if the movie we’ve been watching hasn’t been especially interested in exploring that angle. On the other hand, it’s nice that Workman doesn’t try to overinflate the importance of the stunt. Sometimes a secret mall apartment is just a place to play video games and plan your next act of guerrilla art with your pals.

Youth (Hard Times) (2024)

Youth (Homecoming) (2024)

The Japanese film critic Nanako Tsukidate is a legendary hater. If you invite her to submit scores to a film festival critics grid you’d better be prepared for her to lob one- and even zero-star reviews at otherwise warmly received movies. Her hatred is not without its own internal logic. Writing about this year’s Cannes Film Festival, for instance, she expressed displeasure at the state of global film financing. Increasingly, she notes, film festival sidebars are becoming launching pads for exclusively European productions, while even films from outside the continent are largely co-financed by French or American production companies. Truly homegrown productions are, if not rarities, then at least not given the same shot at reaching an international audience.

Each film in Wang Bing’s documentary trilogy about young sweatshop workers (the first of which I covered last year) opens with the marks of international money: alongside recognizable French production company stingers, we’re also told that Bing got money from Dutch and Luxembourgish financiers for his project. The end credits of each film inform us that Bing shot the project between 2014 and 2019; altogether, the trilogy runs to a little under 10 hours. I don’t know where all the money went (or how much the budget for the project totaled in the end) but this is one of those cases where it’s probably fair to say that it’s all visible onscreen.

Whereas the trilogy’s first installment, Spring, runs on buoyant, youthful energy, Hard Times does what it says on the tin. This is one of the most difficult movies I’ve ever sat through. For three hours and 45 minutes, Bing follows the workers at various clothing workshops through some of their most challenging interactions with their bosses. In the first segment, a kid loses his timesheet and has to try to convince his unmoving manager to pay him what he’s owed for labor performed. (He doesn’t get far.) Before giving this story any resolution, Bing cuts to another shop as the workers are finding out that a man has had his head bashed in right outside their building, just for asking his bosses to pay up for money they owe him. There’s no way to tell if this is the same guy we were with before, but that’s immaterial; in this province of some 18,000 sweatshops, the stories of the workers all start to bleed together (figuratively…though in this case literally). The workers, ranging in age from 15 to 25, all live onsite in facilities that are cramped, poorly lit, and piled high—like, overflowing—with garbage. It’s amazing any of them are able to work up the will to collectively bargain for better rates (as we see some of them do), especially given how easily the bosses can just flee with the money and threaten their workers with immediate eviction.

Homecoming is the shortest entry in the trilogy, at a mere two and a half hours. The centerpiece of the film follows a worker to his rural hometown for a New Year’s holiday and a wedding. It’s unclear that sweatshop life is any better than home life—back in the country you at least get home cooking more regularly—but if anything’s certain it’s that there’s no money to be made back home. It is a bit of a relief for the viewer, at least, to get to spend some time in the open air, but it isn’t long before the movie drags us back to the shops for more of the same. Is the monotony of the trilogy punishing, or is it an extreme bid for empathy? There comes a point in the films where you want the filmmakers to reach out and do something, anything, to help some of these kids out (this isn’t an interview-driven documentary, but sometimes the subjects do talk back to the camera). Apparently there’s enough money in the world of film financing to get these images of capitalism’s refuse in front of audiences privileged with time enough to sit through them all1. How much more would it take to furnish the workers on camera with living wages and a cleaner environment to live in?

(For whatever it’s worth, Nanako Tsukidate gave Youth (Homecoming) a generous three and a half stars out of five.)

Afternoons of Solitude (2024)

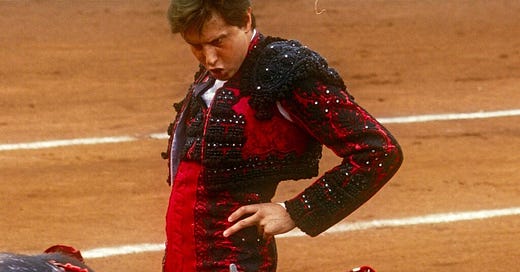

The latest Albert Serra stomach-churner reminded me of Dutch portrait photographer Rineke Dijkstra’s series of bullfigthers. They’re all staged pretty much the same: floral coat, white shirt, skinny necktie, facing the camera at an angle, decorated in blood. They’re also all, for the most part, kids. Of the many questions raised by these portraits, the one that jumps out is: who let you do this?

The bullfighter Andrés Roca Rey would have been 26 or 27 in the year that Serra shot this documentary about him. I had to look that up on Spanish Wikipedia to figure it out, since Afternoons of Solitude is the type of doc that dispenses with anything that qualifies as “information.” Serra’s camera follows Rey into the bullfighting ring, into the party van that ferries him out of the ring, and on one occasion into the hotel room where Rey gets suited up for the ring (it’s a two-person job to get into the toreador outfit, a look that falls somewhere between glam rock and drag race). If you wanted to watch bullfighting at home I guess you could do that on TV (maybe? I don’t know if these things are actually broadcast in America), and you would probably actually get a better sense of how it works that way. In Afternoons of Solitude you never even see the size of the crowd at any of these events (though you certainly hear it) because Serra shoots much of the film in outrageously close close-ups, turning the man-versus-bull battles into primal abstractions of primary colors.

Bullfights always end in death, of the bull or of the matador. Because Serra has no scruples about showing this, or any of several unanticipated near-death experiences, I can’t recommend Afternoons of Solitude to most people; however, for those who value aesthetic virtues, it must be said that this movie (like all of those Serra has shot on Blackmagic pocket cameras with DP Artur Tort) looks totally unlike anything else being made today. Without any biographical or historical context to grab on to, the viewer of Serra’s film is left with questions of performance, spectacle, and ethics. One such question I haven’t decided how to answer yet: is it even okay to watch this?

Rey has a team of hype-men who gas him up before, during, and after the fights, feeding him an idea of masculinity predicated on the unsettling combination of killing a large and innocent animal after tauntingly prancing around it in sparkly clothes and tights. Judith Butler’s famous dictum, that “[t]here is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender” feels applicable here—Rey constructs a version of masculinity by performing it over and over in the ring—or maybe moreso the line of Nietzsche’s that Butler is riffing on: “there is no ‘being’ behind doing, effecting, becoming; ‘the doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed—the deed is everything.”2 Neither glorifying, contextualizing, nor moralizing what he finds in the world of bullfighting, Serra has created a perfectly Nietzschean artifact of a ritual that refuses to die and the young men that get fed into it at risk of their lives.

The Perfect Neighbor (2025)

A few years ago Ajike Owens, mother of four, was shot and killed by her Florida neighbor Susan Lorincz. The story got out to Owens’s extended family, one of whom was a film producer who teamed with director Geeta Gandbhir to make a movie memorializing Owens and drawing attention to Florida’s stand your ground laws. With little else to work with for telling the background to this story, the filmmakers decided to turn to surveillance footage from the night of the shooting. A couple of FOIA requests later, what they ended up finding was nearly 2 years’ worth of body camera footage from police visits to Lorincz’s house as they responded to her every petty grievance about the neighborhood kids.

The police in this movie are “doing their jobs” in the sense that they don’t outright kill anybody, but they’re failing in their duty to deal with Lorincz appropriately. Lorincz is clearly unwell—one of her neighbors speculates schizophrenia, and Lorincz herself wields her past traumas as a constant defense of her erratic and overblown behavior. This movie isn’t saying whiteness is a mental illness but Lorincz clearly feels racially entitled to use the police as her own personal cavalry every time things aren’t going her way. (So, really, the police are doing their jobs in the sense that they’re serving the interests of whiteness.) You can easily imagine a hundred different ways Lorincz might have dealt with annoying neighbors, starting with, oh I don’t know, showing some actual neighborliness. When you turn your house into a private citadel, everything outside it necessarily begins to look like a threat.

Yeah, yeah, guilty as charged.

Via The Genealogy of Morals, as quoted in Gender Trouble.

![Afternoons of Solitude — Albert Serra [NYFF '24 Review] | In Review Online Afternoons of Solitude — Albert Serra [NYFF '24 Review] | In Review Online](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Negv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7c568e67-2682-463b-bd06-26b7b40a5caf_1024x579.jpeg)