Watching

Compensation (1999 / 2024)

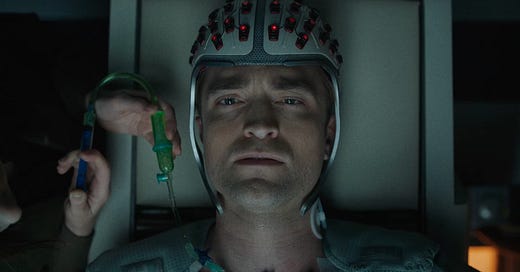

One of the most fun parts of the city of Rome is the visible layering of history. Here’s a Renaissance church built atop an ancient Roman catacomb, there’s an ancient Roman temple built over an…even more ancient Roman temple…and so on. The version of Zeinabu irene Davis’s 1999 film Compensation that’s been touring select theaters is of similar archaeological interest, in cinematic terms. Billed as a “rejuvenation” instead of a restoration, the film is a 4K transfer, yes, so the upscaled 16mm footage is crisp and clear as day. But Davis, working with varied collaborators in the Deaf community (including Alison O’Daniel of The Tuba Thieves fame) has reimagined her film for a contemporary audience of Deaf and hearing viewers alike. What this entails is the addition of new sound effects chosen for the quality of the vibrations they produce and a totally new captioning system that pins descriptions of specific kinds of sounds to fixed areas of the screen and maps overlapping lines of dialogue onto the speaker in space to better communicate who is saying what at any given moment (see the below screencap for an example of how this works). The old film is still the base, but a new(ish) film has been constructed upon it.

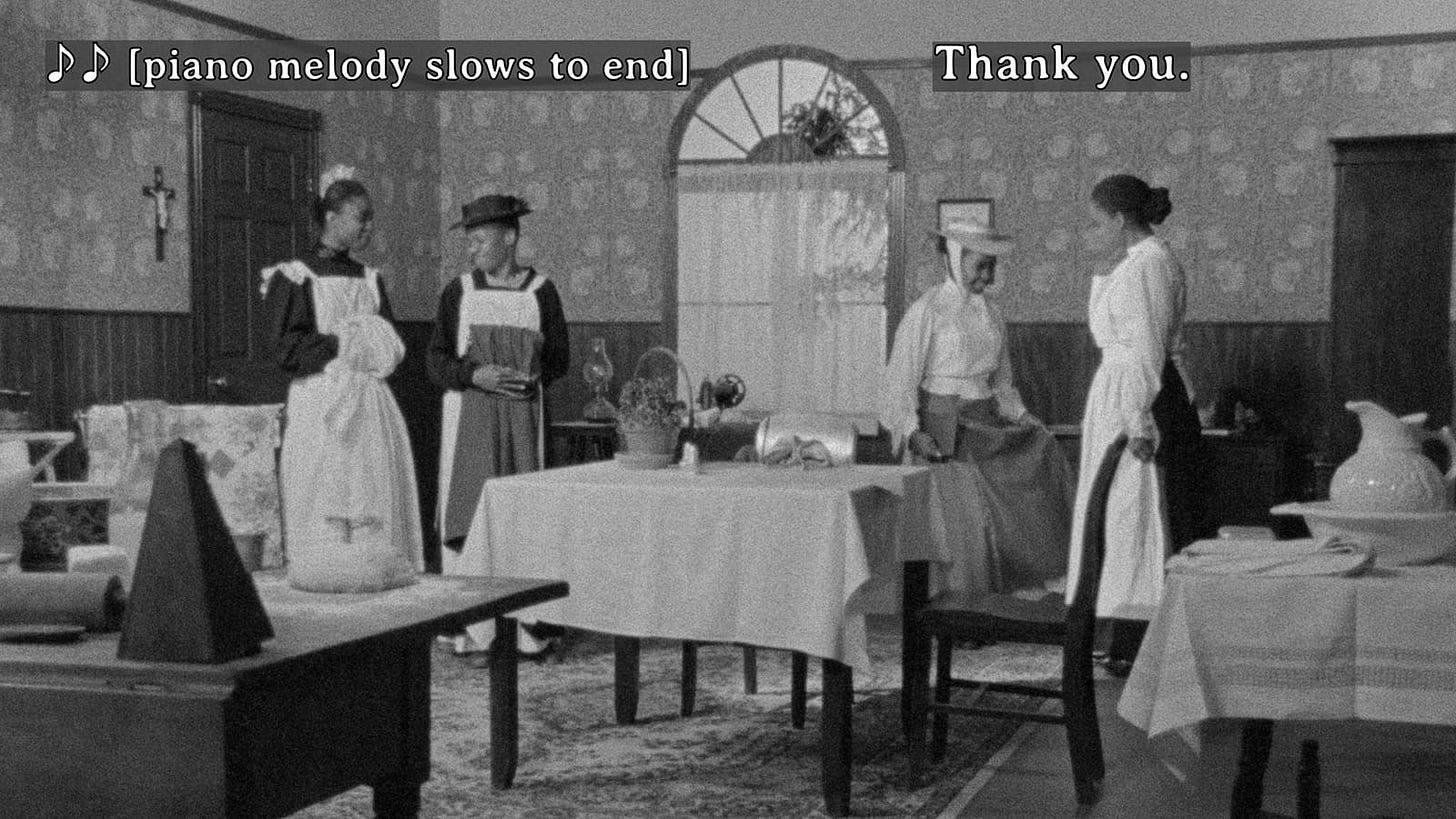

Compensation follows the storylines of two Deaf Black women in Chicago (both played by Michelle A. Banks) living at opposite ends of the 20th century. Their lives rhyme without ever intersecting. In the early 1900s, we follow Malindy, a whip-smart seamstress teaching ASL to a love interest; in the 1990s, we get the story of Malaika, an artist who’s being wooed by a hearing guy determined to learn ASL on his own so he can win her heart. There’s a very plus ça change kind of quality to the movie, which represents the (very) gradual evolution of civil rights for disabled people over the course of a century. Because this is an extremely low-budget film, some things work better than others. For lack of production design dollars, Davis fills the 1900 sections of the film with panning clips of archival photographs. These are still informative, contextualizing historical records, but they throw off the rhythm of the film in a way that becomes noticeable when juxtaposed with the freer-flowing 1990s segments. The movie really comes alive when it’s with Malaika, who unlike Malindy has a richer community of Deaf and signing friends to build a life with. As a study in intersectionality, Compensation probes how marginal identities never really exist in a vacuum; that it does so while feeling more poetic than didactic is all to its credit as an essential, almost-forgotten piece of independent American cinema history.

Black Bag (2025)

Behind every globetrotting, gun-toting, backroom-dealing spy is a team of data analysts spending all day in their cubicles, glued to their computers. I’m actually not even sure that we have globetrotting spies anymore, or if we ever did. Where movie magic ends and the cold hard truth of the intelligence community begins is not a distinction I feel qualified to make, but I feel fairly certain in declaring the office politics at the heart of Black Bag a closer mirror of the real thing than anything you’d get out of a Bond movie.

George and Kathryn (Michael Fassbender and Cate Blanchett), the spy couple at the heart of Steven Soderbergh’s David Koepp-penned new romp, have been in the intelligence business a while, long enough to have built a home together in a London rowhouse with one of those creatively expensive kitchens (one entire wall is glass, facing out onto a micro-courtyard, but who’s keeping track). As cohabitating colleagues, they inspire awe in their junior coworkers (please forget for a moment that Naomie Harris is actually older than Fassbender), who have been trying to lock down their own work spouses with much less success. As the movie opens, George learns that Kathryn is on a shortlist of spies who may be up to something treasonous, so out go all the work–life boundaries as he snoops around to find out if she’s keeping anything from him and, later, to collude with her in what she’s really up to.

Black Bag won’t compete for any awards 10 months from now (though the jazz band with generalized anxiety disorder in David Holmes’ score is rather nice), and most viewers will forget it and move on quickly. Soderbergh at this point in his career is never going to shake the allegations that he makes technical exercises instead of films and while I haven’t seen any of his last…10? movies for a reason, I would think that some of the filmmaking here—like a crosscutting quadruple polygraph sequence—would get at least a begrudging nod of appreciation from the haters. This film reminds me of nothing so much as the similarly-brisk noirish potboilers of the 1940s and 50s. Take the stuff of everyday life (romance, jealousy, work), raise the stakes, cast some beautiful people and give the camera to somebody who knows what to do with it; this isn’t The Third Man but neither were most movies released in 1949.

Mickey 17 (2025)

Bong Joon-ho has made three great films. Mickey 17 isn’t one of them. Adapted from Edward Ashton’s sci-fi novel Mickey 7 (where’d the other 10 come from?), director Bong’s new film retreads all the same themes animating his earlier work with none of the same humor, pathos, or memorable set pieces. Mickey 17 lives and dies on Robert Pattinson’s performance as an “Expendable,” a sort of living crash-test dummy on a spaceship crew setting out from Earth to colonize a distant planet in an ambitiously near future (only 30 years from now to develop all this technology feels like a stretch). Pattinson’s Mickey has signed away his life rights to science, so that when he dies performing perilous tasks, his consciousness can be re-uploaded to a new, replica body. You, the viewer, know you’re in trouble early on, when Pattinson begins to narrate everything that’s happening and doesn’t shut up for another 30 minutes. The movie’s better off whenever it just lets Pattinson act with his whole person, which, thanks to the drearily long runtime, he has more than ample opportunity to do.

Mickey 17 takes the idea of the company that wants to own every facet of its workers’ lives and stretches it to an absurd breaking point. If capitalists could find a way to work you to death and then bring you back to life to do it all again, you better believe they would. Interestingly, there’s little mention of AI in this movie (was there a Butlerian Jihad?)1 so Mickey 17’s message about the future of labor confused me a bit. Workers do worry that they’ll be made expendable (because of AI), but not that our labor power will become infinitely exploitable in quite the same way that Mickey suffers. I guess you could say Mickey’s plight is a comic exaggeration of the way that companies wave around, say, wellness benefits to keep rejuvenating their workforces after bleeding them dry of their labor power. Or this could all just be a bit half-baked; I’m not feeling too generous today so I’m going to go with that.

Since I haven’t read Ashton’s novel, I don’t know how much of the film is a direct adaptation versus what’s a supplemental pet interest of Bong’s. See: the entire vegetarianism-boosting subplot about interspecies relations ripped right out of Okja. The “creepers” inhabiting the planet-to-be-colonized are somewhat cute, somewhat gross, a little threatening when they need to be. The biggest reaction this movie got out of me happened after it was over, when I found out that the notoriously husky Anna Mouglalis provided the voice of the creeper queen. That’s the kind of perfect casting you just can’t replicate with AI-generated voiceover, which I’m sure Warner Bros. was begging Bong to use to keep costs down.

Eephus (2024)

I’m happy for all the people for whom Eephus was made. Maybe that even includes me! It’s true what they say about baseball being our national pastime: unbelievably, I’ve been to high school, minor league, and major league games. Plus, Eephus was shot in Douglas, MA, so as a proud child of the Bay State I’m required by law to give it a positive notice in my newsletter. Eephus is a wry entry into the sports-movie canon, condensing the length of a single, daylong game of rec ball into the space of some 90 minutes and shooting the proceedings from consistently interesting widescreen vantages to keep things from ever getting boring.

Real sportsheads probably won’t have any trouble keeping track of the large cast; I have to admit I couldn’t keep up with who was who and just sort of let the ensemble work wash over me. (I was pumped, however, about the movie’s “featuring the voice of Frederick Wiseman” credit and only wish we had gotten more of his gravelly-voiced radio announcer.) You can tell that Carson Lund, making the jump to the director’s seat after a series of indie cinematography credits, feels fondly about these guys, warts (physical or figurative) and all. This is a farewell game of ball, the last these men will ever play on this field before it’s demolished to make way for a school. There’s a bit of a bait-and-switch going on there—a more leaden, obvious screenplay would have swapped the school for a luxury apartment complex and made this a story about gentrification. Instead the script makes the movie all about the disappearance of sporting leagues as an inclusive and intergenerational way for men to hang out, get out of the house, and engage in some communally-sanctioned rivalry. When the sun fully sets and the guys drive their cars onto the field to keep it illumined by headlights, it would be hilarious if only their desperation to keep the game going as long as possible weren’t so palpably sad.2

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl (2024)

Shula (Susan Chardy) has the look of a woman who can’t just live her life how she wants—people keep getting in the way. One night on her way home from a party, the happiest she’ll look all movie, she drives by a dead body on the side of the road; it’s her Uncle Fred. Cue the thousand-yard stare. As Zambians, Shula’s family observes elaborate and culturally mandatory mourning customs. The whole extended family eats, sleeps, and wails in the house for days; no one is allowed to bathe until after the funeral. Before Shula even makes the first phone call to tell her dad that Fred’s dead, the events of the week to come flash before her eyes. Fred’s family is lower class, so Shula’s middle class home will be the site of all the proceedings.

On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, following 2017’s I Am Not a Witch, continues director Rungano Nyoni’s nascent series of feminist films about young African women struggling to break free from the molds that country and culture want to place them in. Interestingly, it’s women who run the show in this film, specifically the aunties. An endless parade of women who are all somehow related to Shula completely take over her life, commandeering her home for funereal rites, putting her on kitchen duty, following her to the hotel she attempts to escape to so she can do her job (there’s a Zoom meeting jumpscare that quietly underscores how Shula has one foot in her home country’s way of life and another in the world of global capital; she’s on her way to turning out like Sandra Hüller’s character in Toni Erdmann, but with a much less helpfully mischievous father to save her from turning into a mirthless corporate drone). When Shula goes to bring the news about Uncle Fred to her cousin Bupe (or at least I think she’s a cousin), she finds Bupe barely conscious in her dorm room bed with an explosive iPhone confessional video awaiting discovery nearby.

It turns out all the young women in the family have their own Uncle Fred stories, and they’re not the kind you recount lovingly in a eulogy. Nyoni addresses the history of sexual abuse in the family from two angles: from one, she investigates the long-reaching impact of sexual trauma on Shula and her cousins; from another, she interrogates the role of the older women in keeping up appearances and making excuses for an otherwise beloved abuser. What makes this a tough sit is the knowledge that there’s no easy way out of this mess—although the title (which is eventually explained) suggests one way toward a more accountable family structure. Word gets to the aunties that the girls have been chatting, and Nyoni stages a cross-generational confrontation. It ends in tears both bitter and relieved, but the catharsis doesn’t feel right in the moment and the film even proceeds as though it didn’t happen. Offering her characters and audiences temporary relief is a welcome grace, but Nyoni’s film is strongest when it sits with the discomfort that pervades communities still working their way toward justice.

I was listening to people talk about this movie and someone suggested that AI does get used as a deus ex machina to produce an instant translating device, so I’ll grant that the movie has one specific use case for it but we’re generally not seeing machine learning replace most human labor.

What is hilarious (to me): according to Wikipedia, Lund modeled Eephus after Goodbye, Dragon Inn. I can (sort of) see it!