Watching

They Do Not Exist (1974)

In 1974, a familiar scene: after a terrorist attack on an Israeli school by Palestinian guerrilla fighters, Israel responds by razing a refugee camp of Palestinian civilians living in Nabatieh, Lebanon. Filmmaker Mustafa Abu Ali, born in Jerusalem and educated in London, Berkeley, and under the tutelage of Jean-Luc Godard, was at the camp and filmed the before and after. Thus, some sources say, was the tradition of Palestinian filmmaking born.

They Do Not Exist runs to only 25 minutes—an additional, final minute has been lost—and opens with scenes of life in the camp before the bombs fall. Women fold laundry and water the plants while children eat popsicles and frolic in the alleys; traditional, upbeat Palestinian instrumental songs accompany these sights. Contrast these opening minutes with the ensuing sequence of the air raid. Unnervingly scored to a Bach concerto, the footage of the bombings is intercut with quotations from prominent Zionists proclaiming the nonexistence of Palestinians, whence the title of the film. The film wraps with interviews with the refugees amid the wreckage. Along the way, Abu Ali interjects some polemical editorial statements about colonialism’s destruction through the ages.

In his introduction to the 2006 essay collection Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema, Edward Said offers a hypothesis: “the whole history of the Palestinian struggle has to do with the desire to be visible.” For people like the Palestinians, historically the victims of forced displacement and racism, visibility has vital stakes; it’s a challenge to the invisibility foisted upon them by the colonial powers that stand to benefit materially from their disappearance. They Do Not Exist stands athwart the dehumanizing tactics of Zionists and makes the case for the humanity of the lives lost and dislocated at Nabatieh. Just as courageously, it links arms (so to speak) with all who have suffered from imperialist violence, from the indigenous people of the Americas to the victims of the Holocaust, rejecting the view that the genocide of Palestinians is a tragedy that can be fully understood in isolation.

The Dupes (1972)

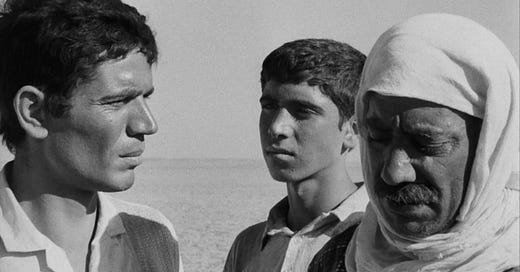

Even before Palestinians began filming their stories themselves, their situation interested other filmmakers in the Middle East. Take the Egyptian director Tewfiq Saleh, whose film adaptation of the 1962 book Men in the Sun, by Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani, was one of the earliest features where Palestinians were the protagonists rather than sidelined bit players. The Dupes was restored last year by the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and if it can get in front of more eyes I could easily see it being hailed as a rediscovered classic.

The titular Dupes are men from three generations of Palestinian refugees, each in search of opportunity but lacking the means to escape their present impoverished circumstances. Each man has a unique relationship to Palestine, established by Saleh in the film’s first half with smooth-as-silk crosscutting between past and present, including an extended montage of documentary photographs. Word has it that there are jobs in Kuwait (though no trees, as a driver gruffly informs the oldest man of the group, who is nostalgic for the felled trees of his homeland). The back half of the film is a dirt- and sweat-filled operation to smuggle the men across the border, a masterfully paced suspense thriller through a pitiless desert. The title of the film basically sets you up for how this is going to end.

With the exception of one guy shown in a flashback (where he dies), The Dupes is devoid of characters who rise to the level of heroism. Saleh had his reasons for avoiding uplift and encouragement. In a 1976 interview, he explains his viewpoint:

Traditionally in revolutionary films, it’s the strong characters who provoke change. Not so, of course, in The Dupes. It primarily focuses on weaker people who seem crushed by fate, but shown in such a way that the audience can’t help but learn from this depiction and become more aware of the problems through it. Rather than give examples of positive heroes, I prefer to explain to spectators why the ordinary people they see on the screen experience these difficulties. If we want to change the situation, it may be more useful to reveal the causes for this suffering rather than prioritize extraordinary people.

I think this is a fairly gutsy position for a filmmaker to stake out, and it speaks to Saleh’s high level of trust in viewers to be mobilized by The Dupes rather than let it lead them into despair.

Palestinian Women (1974)

Jocelyne Saab, like Tewfiq Saleh, filmed Palestinian stories as an outsider. Saab was born in Beirut and worked as a war correspondent for French television. She would one day make narrative feature films, but her early work of the 1970s comprised short and longform documentaries. Palestinian Women is one of the shorter ones—really short, at only 10 minutes. Intended as a segment for broadcast TV, it was shelved by her editorial department and only resurfaced for public consumption years later.

Palestinian Women reminded me a bit of Agnès Varda’s Black Panthers (1968) and I wouldn’t be surprised to learn if Saab were influenced by it. Saab showcases Palestinian refugee women in Lebanon fulfilling both caretaking roles (teaching preschoolers, for instance) and militant ones (training for combat with kalishnikovs in hand). Saab was very choosy about the images she put onscreen:

It was absolutely necessary to show a new image, another image of the war. It was not simply a matter of throwing an image out to the viewer like we do today, throwing an image of violence that confuses viewers and makes them not know where to stand. On the other hand, when we offer an image, even a very personal one… if it is thought out, if it speaks to people’s emotions, to the pain of others, it allows us to situate ourselves, to know where to place ourselves.

Regarding this pain of others, Saab is quite sensitive to it in what little time she spends with these women. Saab’s interviews touch on everything from the quality of conditions in the refugee camps (not great) to the pay discrimination Palestinians face in Beirut. Regardless of their educational background, the women she speaks to speak about their situations with confidence and vigor, in marked contrast to how the women in films by Saab’s male contemporaries are depicted as quiet and docile onlookers.

Wedding in Galilee (1987)

Here is my experience of watching Wedding in Galilee, which will probably also be yours if you choose to follow in my footsteps. It’s a Thursday night. I throw the movie on; it’s on Youtube, with subtitles even, in a fairly poor-quality transfer.1 What’s a little pixelation, I say to myself. An hour and 15 minutes later, the in-movie sun sets, and the remaining 30 minutes pass in an almost-total darkness punctuated by the occasional shimmer of gray squares. Is the home stretch of this movie supposed to be shrouded in blackened mystery? Who is to say.

Michel Khleifi, the director of Wedding in Galilee, is one of the prominent figures in the aforementioned Dreams of a Nation. He wrote one of the chapters for that book, from which we can learn a bit about his worldview, and the making of this film in particular. If the directors we’ve talked about so far have each been pioneers in their own rights, Khleifi may be the most popular of the founders of the Palestinian cinematic tradition. Khleifi was born in Nazareth in 1950 (two years after the start of the Nakba), but he relocated to Belgium in his twenties to study and work in film production. Many impulses guided his filmmaking: a commitment to the direct cinema movement,2 an affinity for the poor, a conviction that the rights of individual Palestinians are curtailed by the archaic structures predominating in their society.

Wedding in Galilee was Khleifi’s second full-length feature and draws on some of his early-career documentary methods, including a cast of non-professional actors. In the film, a village mayor is marrying off his son, but he must get permission from the occupying Israeli army to bypass the mandatory curfew. The general he gets an audience with strikes the mayor a deal: let some of the Israeli soldiers come and enjoy the celebration, and the wedding can proceed as desired. The rest of the movie follows one long wedding day and night, and is filled primarily with prolonged sequences of the villagers enacting the customary Arab wedding rituals. Aside from all the ceremonial singing and dancing, a group of men scheme to ambush the visiting Israelis; a horse gets loose in a minefield; violence eventually erupts but, as I said, it’s too dark to see what exactly happens and to whom. This is definitely a movie of greater documentary interest than narrative or aesthetic interest, if you ask me. Khleifi might be empathetic when it comes to telling women’s stories, but he’s not going to beat the male gaze allegations. Best perhaps to focus on what he does well: preserve a piece of his heritage for all who care to see.

Yes I’m aware there’s a better transfer out there…

It is a cinematic practice employing lightweight portable filming equipment, hand-held cameras and live, synchronous sound that became available because of new, ground-breaking technologies developed in the early 1960s. These innovations made it possible for independent filmmakers to do away with a truckload of optical sound-recording, large crews, studio sets, tripod-mounted equipment and special lights, expensive necessities that severely hog-tied these low-budget documentarians. Like the cinéma vérité genre, direct cinema was initially characterized by filmmakers' desire to capture reality directly, to represent it truthfully, and to question the relationship between reality and cinema.