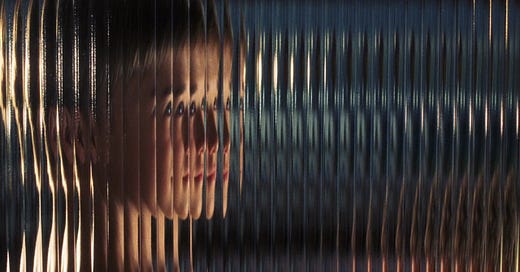

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001)

Artificial intelligence is an umbrella term, so it helps to be precise when talking about it, not that most people are. The technical processes that can outmaneuver a human in a game of chess are distinct from the ones that can churn out a plastic-action-figure rendering of you from a reference photograph, and those from the ones that string together text in what resembles human language, and still those from the techno-accelerationists’ dreamed-of superintelligence that would fill a (surely anthropocentric) god-shaped hole in their souls. Steven Spielberg’s A.I. is concerned with the subspecies of humanoid, artificial general intelligence that we as an organic species have enjoyed fantasizing about creating for hundreds of years, the kind that lets us play God according to whatever we happen to think God is on any given Tuesday.

A.I. isn’t necessarily a movie you turn to, almost twenty five years on, for scientific accuracy. We know now that we’re swimming in it that the types of AI, in all their variety of mechanics and aims, are coming into coexistence on overlapping timelines. The world posited in the Spielberg film, where the only AI in town is of the cyborgian kind (as well as one—quaint!—example of a pay-to-play proto–search engine voiced by Robin Williams), was never going to come to pass as it’s presented. I’m not a science fiction writer myself but I have to imagine that Spielberg and others who confabulate in this genre like to try at least a little bit to predict the future; here there’s a prologue explaining the sinking of Amsterdam, Venice, and New York after the melting of the polar ice caps, but that’s really the only part of Spielberg’s vision of things to come that feels totally plausible. The cars aren’t even self-driving!

After the eco-apocalypse foreword, we’re introduced to this movie’s world of cybertronics at a lecture hall where one Professor Hobby (William Hurt) is holding court before a rapt audience of technologists. It should tell you something important about this guy that he chooses to demonstrate the supposed humanness of his inventions by stabbing one right through the hand with a pin to make her feel pain. Hobby’s robots can walk the walk and talk the talk, but he never met a scientific mountain he didn’t immediately want to climb, and so he announces to his startled colleagues his intention to build a new model robot that can love. Is this the guy we’re really going to trust to know what that looks like? (Well, maybe better him than the guy in the peanut gallery who thinks Hobby is talking about his already well-selling line of sex dolls. But only a little bit better.)

A fitting test family for the first love-capable robot is found in the new-money-chic couple Monica and Henry (Frances O’Connor and Sam Robards), whose son Martin (Jake Thomas) has been in some sort of accident that has earned him an indefinitely long stay in a cryochamber for the comatose. On a routine visit to their son’s podside, a doctor pulls Henry aside while Monica is reading Martin a book and gives him the wild idea of recentering his wife’s grief (with the help of a robot) to help her process the disaster and move on. Spielberg’s camera lingers on a painting of the fable of the emperor’s new clothes in the background, which is both an on the nose reflection of what the scientists are up to in this movie and also a totally insane thing to paint on the walls of a children’s coma ward.

Monica initially protests when Henry brings home David (Haley Joel Osment), a first-generation childlike mecha, for a trial run. After a period of adjustment (in which David barges in on her on the toilet while she’s reading, menacingly, a book titled Freud on Women), she decides to initiate the protocol that will cause David to imprint on her. I don’t think that’s quite the same thing as loving her, but I guess Dr. Hobby didn’t think that all the way through. Amazingly though, Monica ends up warming to David’s constant dotage. Even after Martin makes a miraculous recovery and reclaims his place above David in the family hierarchy, Monica can’t shake her reciprocal feelings of lovingkindness for her robot surrogate son.

When Dr. Hobby presents his harebrained idea at the start of the movie, a skeptical scientist asks him how he plans on making humans love robots back. This is the question explored through most of the movie, when it isn’t tied up in the Oedipal drama. The domestic first act segues into an adventure quest of a second act, wherein David encounters the world of people who don’t take very kindly to the presence of mechas in daily life. David gets caught and brought to a “flesh fair,” where a variety of adult-sized robots are all subjected to cruel and unusual tortures before a raving crowd of human circusgoers. Judging by their parts and attire, most of the robots filled service functions: chef, nanny, sex worker (in that last category is Jude Law’s Gigolo Joe, who becomes David’s companion for much of the rest of the film, a Pinocchio-inspired quest to find the wish-granting Blue Fairy of legend). This feels to me like the most resonant part of the movie by the standards of today, when it’s in vogue to talk about Luddites again and to fret anxiously over capitalists putting people out of work with their latest resource-guzzling toys.

A.I. starts out as a very warm movie visually; Spielberg and DP Janusz Kamínski revel in every opportunity they can get to bathe David and Monica in warm light through the home segment of the movie. It ends quite literally as cold as you can get, 2,000 years further into the future, in a new ice age. David, somehow still retaining a charge after all that time (this movie is very light on the specifics of how anything works), awakens to a spelunking team of mecha explorers with the fanciest new firmware who grant him his heart’s desire to be a real boy to see his mommy again. In a post-The Fabelmans world, it’s hard not to look for extratexutal meaning in this story in light of Spielberg’s own relationship with his mother, fraught and fractured as his home life was. Strictly in the world of the text, this coda is a freaky diversion (the movie could have easily ended twenty minutes earlier, when David finds his Blue Fairy in the submerged Coney Island fairground). David, by design, can’t grow old. He might be able to learn (again, the specifics are foggy), but it seems unlikely he would ever be capable of progressing past the puppy love he’s been programmed to display toward Monica.

I wrote “feel” in that last sentence originally then caught myself: all we know of David are his outputs, which may give the appearance of feeling but are still rooted in mechanical structures quite different from humans’ organic ones (to hammer this point home, the movie includes a sequence where David has to be taken apart for repairs after ingesting spinach, his metal innards on full display). Brendan Gleeson’s ringleader character at the flesh fair warns the circusgoers not to be fooled by appearances: the artistry that made David resemble a real human being is impressive, but he’s still just a simulacrum. (Spielberg and team are, it must be said, very good at creating seamless simulacra for any scene where robots are disassembled.) Describing how David reacts when Monica initiates the imprinting mechanism in his circuitry as “love” is to forget the role that metaphors are playing in our understanding of AI. Worse, it’s to forget the power of marketing. Toward the end of the movie David encounters the packaging for an entire suite of Davids (the female models are called, questionably, Darlenes). Nothing that can be bought and sold this way was ever made with altruistic intentions; the cruelty being performed here isn’t on the mechas who will never love as humans do but on the susceptible humans who will part money for them.

Paper Man (1971)

After watching the most obvious movie about AI I could have possibly picked, I wanted to take a look at something a little less mainstream. Paper Man has only been logged by 325 people on Letterboxd so that seemed sufficiently obscure. In it, four grad students come into possession of a credit card mistakenly issued to someone who doesn’t exist, and rather than just use it like a normal amoral person would, they cook up an entire persona for the phantom cardholder using the supercomputer in the lab where two of them work. To make the plan foolproof they need a little extra programming expertise, so they call in a young, big-haired Dean Stockwell to put the finishing touches on the code. This works (I don’t exactly understand how) until the computer starts killing them off one by one. Trigger warning, I guess, for anyone with fears of being offed by a malfunctioning elevator.

This movie doesn’t rise above the quality of any other B-thriller, but it does a few things with the AI element that are worth commenting on. First, the machinery behind the serial killer computer is front and center and not an afterthought. It’s appropriately computer-sized and -shaped, which by 1970s standards means it takes up an entire wall. Whenever the computer does something fishy elsewhere in the building, we cut back to the mechanical behemoth in the basement lest we forget all the circuitry required to execute the murders. Paper Man is generally uninterested in personifying AI, and the only time it comes close is when the computer seizes upon a nearby medical dummy to enact a killing (rather than stick things out in this “body,” the computer just blows it up).

Secondly, the film is pretty clear that the computer only behaves as it does because of directives a human gave it at some point. What happens when a computer becomes self-sufficient, no human input necessary, is the note of terror the movie ends on, but before we can get there the movie goes out of its way to demonstrate how code is destined to replicate the flaws of the people writing it. This is a rather prescient take on AI for 1971, which only begs the question of why this is still a problem 50 years later.

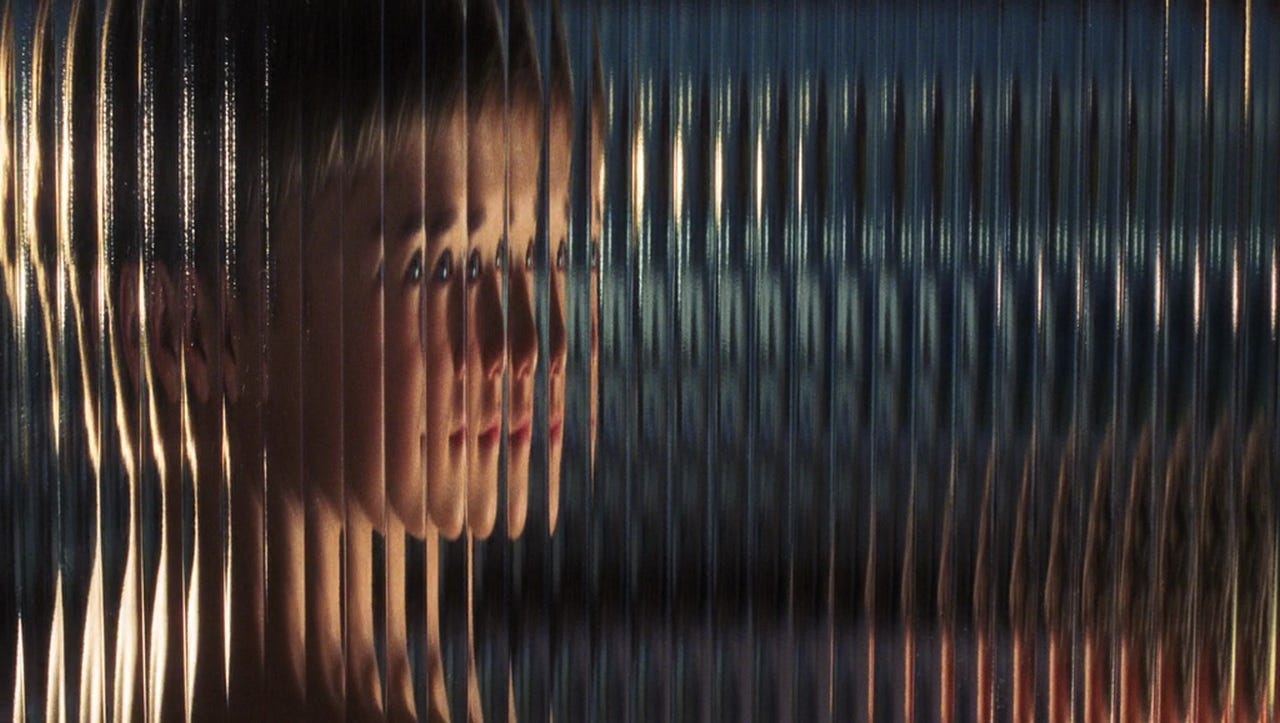

The Shrouds (2024)

The other day I was listening to an interview with an AI booster who, among other things, was jazzed about the opportunities of emergent digital avatar technologies. My response to the idea of (for example) creating an avatar of yourself to learn German so it can give people German lessons anywhere in the world and bring in some passive income was basically, Sure Jan. Well then a similar technology shows up in David Cronenberg’s new movie so I suppose I have to write about it.

Context: Vincent Cassel plays a Tesla-driving tech mogul who’s invented a technology that allows people to monitor the decaying bodies of their deceased loved ones from monitors built into their tombstones (or from an app for an on-the-go grieving experience). He basically built this for himself, after his wife died from cancer. Throughout the movie he’s shown using an AI assistant named Hunny who vaguely looks like and definitely has the voice of his wife. The always uncomfortably sultry-sounding Hunny can be called up from phone, desktop, or car; she can change form from animated human woman to koala bear (as a joke) or to decomposing human woman (also as a joke—Cronenberg has a very particular brand of humor).

Hunny composites a few different things the AI boosters promise these avatars can do. She talks like a human. She talks with the reconstructed voice of a dead one. She seems capable of complex problem-solving. The only problem, as is revealed late in the movie, is that she’s more prone to interference than appearances initially let on. Everyone in this movie is a conspiracy monger of some sort and one character issues a warning that Hunny appears to have been hacked by the Chinese. Unclear if that’s actually the case but more pertinent to my concerns here is the late-film revelation that Hunny isn’t actually a self-sufficient program: rather, she’s being controlled almost fully by some schmuck from his living room. The exact mechanics of this aren’t explained and the more you think about it the less sense it makes (what happens if she’s summoned while he’s in the shower?). In any case, there’s a through line running from this movie back to movies like Paper Man, where the concern around AI being used to nefarious ends is tied up with as-yet unresolved worries about how the human intention powering AI bears responsibility for the bad that computers do.

The Artificial Humors (2016)

All this talk of AI can be unsettling so why don’t we end on something lighter? This Gabriel Abrantes short film is a sketch of the life (“life”) of Andy Coughman (get it?), a floating volleyball-esque robot with great big anime eyes and a squeaky voice to match. Andy lives in some far off quarter of the Amazon with his inventor Claude, who has programmed him with state of the art emotion-recognition capacities and a bit of a Wittgensteinian worldview. One day Andy professes his love for one of the local girls to the village elders, who are having none of this bullshit and send Andy and Claude packing back to Sao Paulo. Claude can’t have Andy going all lovey dovey on her watch so she reprograms him to be the world’s first stand-up comic bot. He does a decent job of it!

Abrantes is a known film purist, and he blends the pleasing texture of the photography quite well with the Andy special effects, which look to be mostly practical (just don’t ask me how they do the levitation, that’s not my wheelhouse). But you can’t help but be a bit exasperated by this movie in the end. We don’t get to artificial general intelligence without a thousand task-specific intelligences along the way, but you’d never know this from watching movies about AI. I fully understand that the robot-with-a-conscience plot is a more eminently cinematic type of story than a “what happens when emergent nonhumanoid technologies destabilize humans’ very capacity to think” kind of tale but from where I stand in 2025 that is the AI story that seems worth telling. And now that I’ve typed it out, it sounds totally reasonable to make a movie about this very real predicament we’re in! Somebody fax a pitch over to Soderbergh and I’m sure he could turn around a tight 90 minutes on the subject for us by Christmas.